The railroad arrives in West Liberty

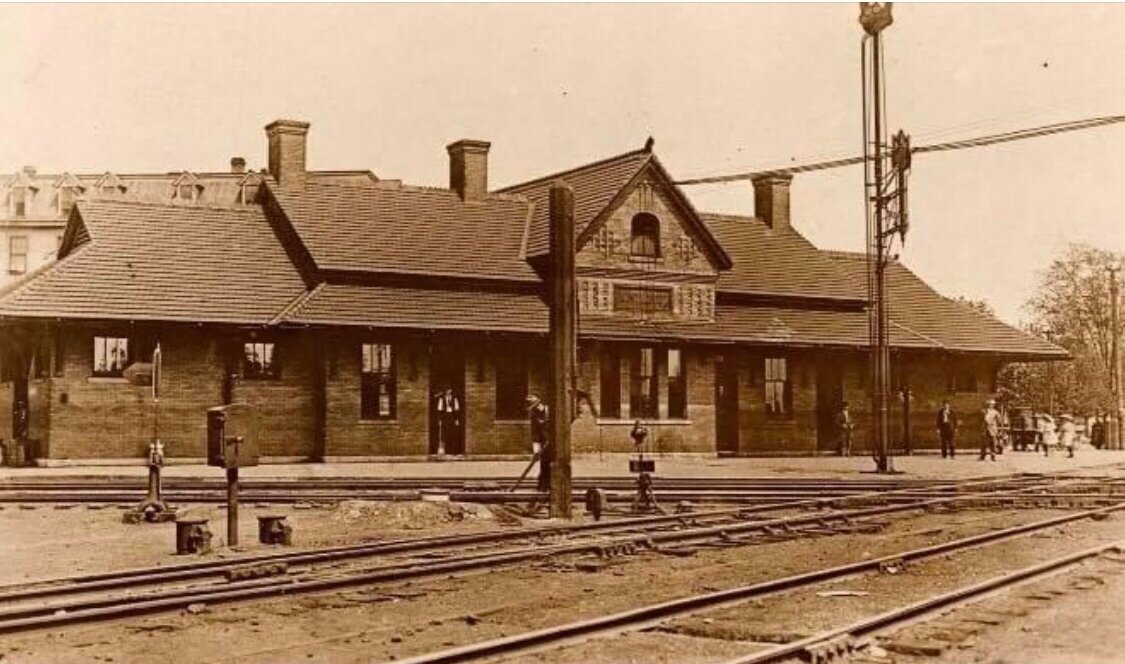

The West Liberty Rock Island Depot, certified by the National Register of Historic Places

The Rock Island Depot of West Liberty was part of the evolution of the rail industry. From steam locomotives to diesel engines, from rail being the prime mode of passenger transportation until its demise, from the days of kerosene lanterns and manual switches to electric lights and electric switches.

From the glory days of the Rock Island to its eventual bankruptcy in 1980, this depot saw much. When the depot was finally boarded up in the late 1970s, it was used for a while mainly as a maintenance shed for rail workers and some limited storage.

Crossing the Mississippi

Because of its connection to eastern cities via railroad, in 1853 the city of Chicago became the major financial, industrial, and transportation center of the Midwest.

From there, various railroad companies competed for expansion to western destinations, with sights on the ultimate goal of completing a transcontinental railroad.

For many of these companies, this involved crossing the very young state of Iowa. The first step would be to reach and cross the Mississippi.

According to information found in a document published in 1898 by the Burlington, Cedar Rapids, and Northern Railroad, it was the Chicago and Rock Island and affiliated interests which backed the Minnesota and Missouri Railroad (M&M) in laying track in Iowa.

The Rock Island line built the first bridge across the Mississippi at Rock Island. During the construction, the steamboat companies felt their supremacy was being challenged, so they sought an injunction against the bridge firm.

A couple of weeks after the bridge opened in May of 1856, the steamboat Effie Afton crashed into the bridge causing one section of the span, as well as the boat, to burn.

A then little-known lawyer named Abraham Lincoln was hired to defend the Rock Island.

Following a long court battle, the Rock Island not only won the right to keep the bridge but opened the way for other railroads to cross as well.

Prior to this time, the only way to cross was via shuttling ferries, steamboats, and keelboats. The first railroad depot in Iowa was at the cabin of Antoine LeClaire, an early settler who’d donated some land to the railroad.

It was used for only a short time before it was demolished, and a more suitable building found.

The Race Continues

The race by the rail companies continued, pressing toward the next milestone: the Missouri River. The Civil War slowed down efforts for some, but in 1867, the Cedar Rapids and Missouri River Railroad crossed the Missouri.

With this accomplished, the focus of railroad construction in Iowa shifted from east and west to north and south. Iowa was growing, and Iowa’s farmers were now fully involved in market and commercial production, so it made sense.

Railroad Arrives Here

When the M&M decided to lay track through our area in 1855, it chose what they felt was the most advantageous route.

The earliest white settlers of Iowa had started moving west of the Mississippi in the 1830s, and the city of West Liberty had its origin as part of that movement, with the establishment of a small village by the name of Wapsinonoc.

It was so named because of its location to the nearby Wapsinonoc Creek. The village was located just northwest of West Liberty’s present-day city limits.

Its first post office was established in March of 1838, eight years before Iowa’s statehood in 1846. The railroad made the decision to leave the already established village almost a mile north of its line.

However, a station was established and a syndicate purchased land on both sides of the present-day depot, platted it into blocks, lots, and streets, and it was named West Liberty.

The ‘Portrait and Biographical Album of Muscatine’ later stated ‘the first locomotive wended its way westward through a cornfield where West Liberty now stands.

Then, there was a farmhouse and a barn without the present limits of the town, and where the business part of the town now is, was a cornfield, the cornstalks standing thick and as high as a man’s head.

The only dwelling was the house on the corner of Spencer and Fourth.’ The railroad brought prosperity and steady healthy growth to the community.

John Brown and the Railroad

Interestingly, West Liberty also sat within a region settled by Quakers, whose abolitionist activities included assisting Freedom Seekers along the Underground Railroad through Iowa.

On the west side of Clay Street was an old grist mill which reportedly served as a stop on the Underground Railroad during its early years.

It also served as the setting for part of John Brown’s exit from Iowa. He’d secured a boxcar at West Liberty for travel on the railroad to Chicago in 1859.

The car was to carry Brown and a group of slaves to Chicago via Davenport. They’d spent the night before in West Liberty at the mill.

The next morning, with sympathetic residents looking on, Brown and a dozen liberated slaves climbed aboard the boxcar on an early eastbound train, headed to Davenport. The next day they successfully arrived in Illinois.

CRI&P Formed

In 1866, a new company was incorporated in Iowa called the Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railroad. Due to financial difficulties, the M&M was purchased by the CRI&P later that year.

West Liberty was incorporated two years later on January 1, 1868. The first wood plank sidewalks were laid on the south side of East Third and the west side of North Calhoun.

In 1872, the sidewalk was extended to the railroad depot, signifying the importance of the railroad to the local economy.

North-South Route

In 1870, another line was built through West Liberty: the Burlington, Cedar Rapids, and Minnesota Railroad. It went bankrupt in 1873, reorganized, and became the Burlington, Cedar Rapids, and Northern in 1876.

This north-south route made the community a junction point and a hub for traffic from all directions.

The West Liberty Enterprise reported on October 2, 1880, that "there were 543 freight and thirty passenger cars that passed through on the CRI&P, and 214 freight and sixteen passenger cars passed through on the BCR&N."

By the editor’s estimate, the number of cars passing through West Liberty in a year would stretch from Boston to Omaha, carrying some 4,380,000 tons per year.

The Globe and the Hise

The original depot was a small, nondescript wooden structure. Nonetheless, with many traveling by rail in those days, the depot was busy, day and night, seven days a week. At one time, there were thirty passenger trains that stopped there every day.

Train crews and passengers changing trains invariably crossed the track for a hurried meal at the Globe Café next door.

The Globe, sometimes referred to as the Beanery or the Greasy Spoon, was opened in 1886 with owner Owen Gorman (uncle of George Harney) and was always owned by someone from that family.

Every passenger train had its schedule so arranged that this was a lunch stop - and every train “laid over” here for 30 minutes or so in order that the train crews and the passengers could “get a bite to eat,” a newspaper reported.

The Globe was demolished in 1970. In the early days, there were two hotels adjacent to the depot to accommodate passengers staying over. The first was the National Hotel, built about 1870 by William Hise.

Later, the name changed to the Hise Hotel. It was damaged by fire in 1876 but quickly rebuilt. It passed into the hands of William’s son, Ed Hise, in 1883.

At some time between 1876-1893, the railroad company purchased a hotel building and moved it to the east side of North Elm Street, across the street from the depot, where it became known as the Cottage Hotel.

Eventually, the Cottage Hotel closed. The Hise family’s hotel burned once again in 1893, and during the reconstruction of the building, the Hise Hotel was run out of the then-vacant Cottage Hotel building.

In the early 1900s, a deal was struck with Hise and the railroad to relocate the former Cottage Hotel building and move the newer Hise Hotel to its spot.

In exchange, the depot received the parcel where the Hise Hotel had previously been. The Hise was run by Ed Hise until he died in 1912.

Frank Moylan purchased the business and ran it as the Moylan Hotel for a time before he leased it to others. This building was demolished in 1970. These two buildings would have been many people’s first sights within the community, welcoming them.

1897 Depot Fire

On a warm summer night in August of 1897, a breeze blew over a kerosene lantern at the ‘old, unwelcoming’ original depot, and the building was quickly consumed by fire.

Most furniture, all ticket coupons, and most of the building were destroyed.

The losses were estimated at $2000. Shortly thereafter, the ticket office was moved to the nearby Hise Hotel for the interim period.

The old depot was less than admired by the traveling public; it’s reported.

The Weekly Enterprise newspaper printed in 1881: "It is the most uncomfortable, ill-lighted filthy place on earth. It is fouled with tobacco spit, fumes of old pipes, stumps of cigar and quids of tobacco which roll underfoot… to the extent of occupying all seats, while ladies waiting are poisoned with the foul air of the place, while compelled to stand awaiting common trains. Such a place is a foul blow on the fair face of the two great lines of road whose depot it is."

The original wooden depot was reportedly a similar style as the current depot, just much smaller and much less accommodating.

Volk Plans a Statement

Following the fire, details of a new depot soon emerged. The newspaper reported it was all ‘an improvement which has long been needed, and the traveling public and people of West Liberty are not shedding any tears because of the fire.’

As the depot was located at the crossroads of two major rail lines, it was to be built as a ‘statement depot.’ No time was spared in getting the replacement built. A contractor, John Volk of Rock Island, was hired by the railroad.

Volk, born in Germany where his father was a cabinetmaker for whom John worked as an apprentice, immigrated to the US at age eighteen with his family, settling in Rock Island a year or two later.

Volk was already credited with building over four hundred depots. For the West Liberty project, a crew of fifteen men was sent to survey the work for the new building. The construction cost was $8000.

The heating of the new depot would be supplied by five pot-bellied stoves. It would have men’s and women’s separate waiting rooms and restrooms.

There would be separate offices for the telegraph and ticket agent and freight rooms, and it was to be built with many modern amenities of its time.

Various newspapers described the building at the time as ‘brilliant’, ‘commodious’, ‘modern’ and ‘beautiful’.

The new depot would sit approximately in the same location and position as the original passenger station and wood platform that were lost in the fire.

As it turned out, the new depot’s exterior would be similar to nearby Wilton’s. The fire turned out to be not so much an ill wind for West Liberty but much more so for Iowa City.

Iowa City was to have had a new depot that fall, but now those materials would be used at West Liberty instead.

The turnaround time was very quick: only three months. With Volk’s experience, further aided by the availability of materials already here, including the Van Meter buff brick he’d used on other depots, the project was completed before winter.

Railway Center of the County

The new depot continued to see an increase in passenger traffic, as indicated in this 1910 Index article: ‘The Rock Island station in West Liberty is a busy place between eleven and twelve o’clock each day.

Hundreds of people transfer from all directions here. Between these hours five passenger trains arrive and depart, bringing many travelers, express and baggage.

There is an enormous amount of the latter that passes through and is transferred here. The milk shipments from this point are a big item as well as other stuff.

West Liberty enjoys the distinction of having more trains and better service than Muscatine, the county seat. Our town is the largest in the county outside of Muscatine.

All trains, numbering thirty-five daily, stop in West Liberty while several fast trains ‘pass up’ the Pearl City. West Liberty is the railway center of Muscatine County, and you can go anywhere anytime from here.’

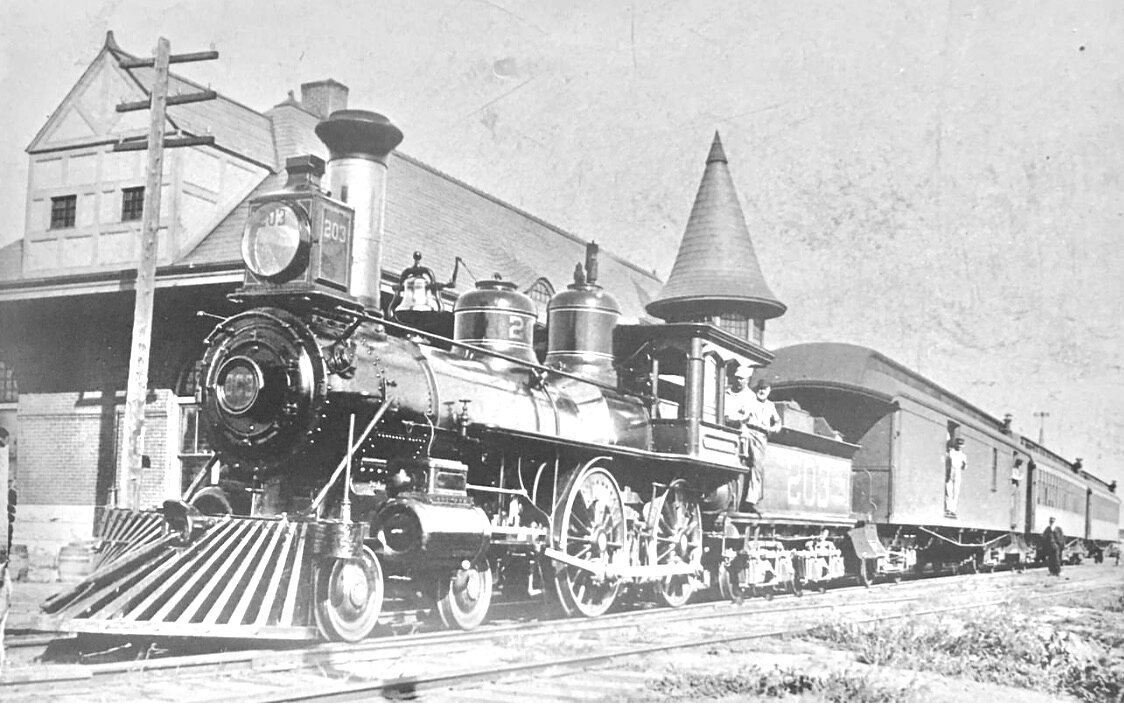

Golden Age of Steam

The period 1880s until about 1920 was referred to as the ‘Golden Age of Steam’ in Iowa. And West Liberty was certainly part of that trend.

The railroad was not only working to build impressive depots but also expanding the rail and increasing the amount of double trackage through the state.

In 1903 the Rock Island line purchased the BCR&N line. A coal chute was built in the railyard. A roundhouse was also built, but was damaged by fire in 1925.

The ruins were torn down and the building was replaced years later by an engine house to house a switch engine.

West Liberty continued to develop commercially, especially along the CRI&P tracks, and along the streets with direct connectivity to the area of the freight depot and passenger depot.

The securing of such a major railroad line plus a connecting branch enabled West Liberty to thrive through the turn of the 20th century.

It was during this period that the commercial district reached its peak, with the construction of more buildings and structures, many of which were built using materials brought in by the railroads. The city’s importance as an agricultural processing center had become well established.

West Liberty had already become known as part of the purebred stock-raising region that encompassed much of northwest Muscatine County.

The large stockyards that lined the railroad tracks on the south edge of the commercial area reflected its agriculture history.

In addition, the many dairy farms of the region encouraged the development of multiple creamery companies locally. It should be noted as well the importance of the railroad during the world wars.

Rail traffic exploded, as much military freight was transported and many troop trains passed through, the greatest number being twelve in one twenty-four-hour period.

Automobiles Arrive

The community boomed because of its position on a very important rail line. However, with the invention of the automobile, highways eventually replaced railroads as the major mode of shipping and personal transportation across the US.

As rail transportation waned, the importance of having and retaining US Highway 6 through West Liberty increased.

As a result, the community’s businesses started shifting away from the depot and the tracks, and more toward the roads.

Cultural History

Despite the slowing of passenger traffic about this time, West Liberty still hosted some interesting moments in its cultural history.

In July 1915, the Liberty Bell was brought through West Liberty on a tour en route to the Panama Exposition in San Diego and made an unplanned stop.

In 1916, on her way to Muscatine, Carrie Nation stopped in West Liberty while on her suffrage campaign tour through the US.

In March of 1919, two trains carrying about four hundred returning World War I soldiers stopped in West Liberty, and the local Red Cross Chapter was on hand with apples, oranges, and cigarettes for the men.

In departing, the men expressed the greatest appreciation for their treatment here, and many promised to return to the town someday. In 1937, the 100-mile-per-hour Rocket Train came through West Liberty.

In 1952, Dwight Eisenhower, then a Republican candidate for president, stopped in West Liberty on his campaign tour through the Midwest.

Other notables stopping in West Liberty over the years included Theodore Roosevelt, Herbert Hoover, and Harry Truman. On a local level, West Liberty’s beloved kindergarten teacher for thirty-one years, Ione Miller, often took her students on an end-of-year train ride to Iowa City.

Steam to Diesel

After World War II ended, the CRI&P was able to convert from steam to diesel.

Back when locomotives were still steam-powered, all trains stopped in West Liberty to take on water from a crane at the depot and got coal from a chute on the east end of town.

Now, coal chutes, a water tower, and a turntable from the old roundhouse were all that remained.

With the coming of diesel, this type of apparatus disappeared from the scene. By 1950, with the automobile causing even more decline in rail passenger service, passenger trains in West Liberty decreased to eighteen trains per twenty-four-hour period.

There were only six trains going north and south and twelve east and west. However, freight travel continued to be heavy at about thirty trains a day.

John Mantor

According to John Mantor (1903-1978), who was a former telegrapher at the West Liberty depot, the freight house and passenger station each had three employees during his time here.

In addition, there was previously a ticket agent. In the 1960s, the railroad eliminated the freight house.

It was sold to the city of West Liberty, moved, and served as a storage barn. The double track was made a single track between West Liberty and Iowa City in the late 1950s. Also, at this time, a remote-control interlocker was installed at the depot.

This made it possible to control from the inside all train movements through the West Liberty railyard.

Mantor also shared that a big board in the station indicated the position of all trains as far east as Atalissa, and as far north as Centerdale, as well as trains approaching from the west. Hence, the handling of trains through West Liberty was speeded up, and fewer brakemen were required.

Since the advent of the diesel engine no longer necessitated stopovers for coal and water, more traffic became ‘through traffic.’ By this time, two-way radio communication was also installed, providing direct contact between the stationmaster and the front and rear of each train.

The Morse telegraph was eliminated by the Rock Island in the 1960s. It was replaced by a telephone system, the radio, and the teletype, connected to a computer in Chicago, Mantor said.

Rail Mail Service Discontinued

By the late 1960s, the government eliminated railway mail service.

This, in addition to an even sharper decline in passenger travel, prompted the Rock Island to start discontinuing passenger trains.

The use of the diesel engine made longer freight trains possible; as the length of the trains increased, the number of trains decreased.

Also, at this time, the number of employees at the West Liberty station was cut to four. Nevertheless, there was never a dull moment for the railroad men.

Every day there were train changes, heavy traffic to handle, and many times derailments and wrecks would occur.

For example, going way back to the winter of 1936, there was a month of non-stop heavy snows, high winds, drifting snow, and subzero temps which caused havoc with train schedules. At times, train movements were impossible. Many trains, both passenger and freight, were bogged down in the snow.

Last Passenger Trains

By the mid-1970s, the future of railroads was looking very bleak. Trucks and planes had been making more inroads on what was formerly solely railroad business.

Many lines, including the Rock Island, were having financial problems and struggled to exist. The last north-south passenger trains (Zephyr and Rocket) came through West Liberty in April 1967.

The last east-west passenger trains to stop in West Liberty occurred in May 1970.

Depot Closes

After the passenger service was discontinued, the depot was used as offices by the railroad freight operations, but the building slowly fell into a state of disrepair.

The depot was boarded up and closed in March of 1980, as a result of the railroad’s bankruptcy.

New Life

The building was rehabbed in the late 20th-early 21st centuries by a group of West Liberty visionaries who decided restoring this unique structure would be an excellent tribute to the legacy of our city.

The West Liberty Heritage Foundation was formed to spearhead this project. Coupled with grant money, donations from residents and businesses, and a lot of sweat equity from volunteers, the 1897 building was restored.

The newly restored structure was dedicated in August 2001 with many notables present, including Secretary of the US Treasury Paul O’Neill. O’Neill’s wife Nancy was a former resident of West Liberty.

The Depot is now a museum to the Rock Island Railroad and the West Liberty community area. The WLHF oversees the property with the help of wonderful volunteers, grants, the Ryan Trust, plus other granting agencies and donations.

National Historical Recognition

The depot during the period 1897-1970 is of particular significance, as in 2022, the National Register of Historic Places certified the West Liberty Rock Island Depot for that time period.

The depot was an important economic and social driver for the city of West Liberty, providing its people and businesses a means of transportation and mail/package shipment in and out of the city.

It also offered employment. For a time, over half of the city’s inhabitants were employed by the railroad.

The depot was also a catalyst for local culture by virtue of allowing visits, even if sometimes very brief, by important political and social figures and other groups.

As Johnny Cash sang in the still-famous folk song about the Rock Island, "The Rock Island line is a mighty fine line."

Comments